We update our review of GDP and GDP per capita following Wednesday’s ABS release of the September national accounts.

GDP grew by 0.6% in the June quarter, tied for the highest growth rate recorded since December 2022. This growth dragged GDP per capita up, reaching +0.2% for the quarter. This is the second positive GDP per capita result in the last three quarters, but only the third since Jun-22 (see Figure 2).

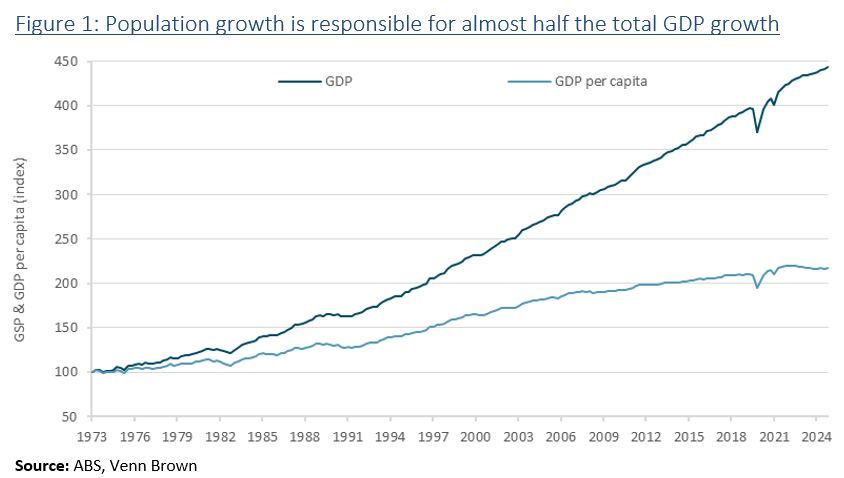

A major flaw in the GDP measure that especially affects Australia is the free kick provided by population growth, which, in Australia’s case, means immigration.

Looking back 50 years to 1973 (when the per-capita series begins), population growth has contributed nearly 50% of the GDP growth, with GDP growing at a 2.9% compound annual rate, compared to GDP per capita, which has averaged 1.5%. Looking over the last 25 years, however, immigration has accounted for a much larger proportion of growth, with GDP averaging 2.7% per year compared to GDP per capita of just 1.2% per year.

Table 1 shows a similar pattern regarding the number of negative quarters and recessions (defined as two consecutive quarters or negative growth). Since September 1973, GDP per capita has registered 58 negative quarters and 19 consecutive negative quarters. Meanwhile, GDP recorded only 26 negative quarters and just eight consecutive negative quarters.

In the last 25 years, the performance gap has widened, with GDP recording only six negative quarters compared to 28 for GDP per capita. However, the starkest contrast is the one set of consecutive negative GDP quarters (COVID, March and June 2020) compared to 9 consecutive negative GDP per capita quarters.

Immigration is the magic lever to which governments (of all colours) have become addicted to boost GDP (and housing prices). If GDP appears to be slowing, simply allow a few hundred thousand more people into the country and watch the GDP grow.

While there was some speculation that the growing discontent with the ongoing housing crisis and cost of living pressures might lead to the end or at least the easing of this policy, the government’s recent announcement of a migration target of 185,000 (inline with 2024-25 target) put an end to that.

No politician wants to be the one who ushers in a GDP-measured recession or, worse still, a meaningful decline in house prices. As such, we do not expect to see a major change in immigration in the near term.

While all the talk focuses on the cost of living and inflationary pressures, it’s worth noting that, despite the government’s proud reporting of unbroken economic growth, GDP per capita has been negative for nine of the last twelve quarters (see Figure 2).

Download the report for the complete analysis.